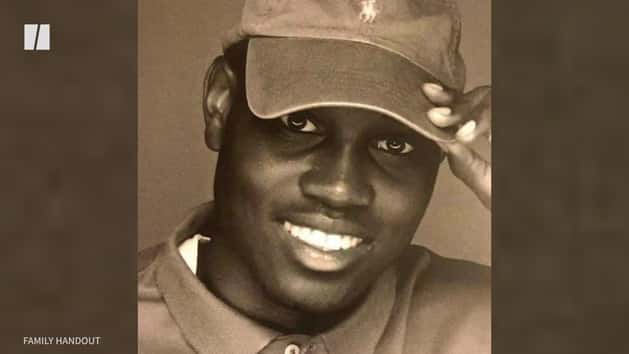

On Day Four of the trial of Ahmaud Arbery’s accused killers, prosecutors played 911 calls Gregory and Travis McMichael made in the months before the Feb. 23, 2020, fatal shooting in Brunswick, Georgia.

Cara Richardson, a 911 center operations coordinator in Glynn County, took the stand Wednesday and recounted the accusations the McMichaels made in calls dating back to July 2019.

Though the men don’t name Arbery, the descriptions they give fit the man they saw running along the road and later gunned down, and the defense has pointed to the calls as evidence that the McMichaels were merely trying to enact a “citizen arrest” on a suspected thief.

Gregory McMichael, his son, Travis, and William “Roddie” Bryan, a resident who followed the McMichaels and filmed the shooting, are facing charges of malice murder, felony murder, aggravated assault, kidnapping and criminal attempt to commit false imprisonment, as well as federal hate crime charges. They are being tried in Glynn County, where the killing occurred.

In the first recording prosecutors played, from the day of the shooting, Gregory McMichael called 911 from the back of a pickup during a chase.

“There is a Black male, running down the street,” McMichael says frantically. The call operator interrupts, asking him to identify where in the Satilla Shores neighborhood they are.

“I don’t know what street we’re on,” the elder McMichael replies. He’s then heard shouting at Arbery: “Stop right there, damn it! Stop!”

McMichael continues shouting as the operator tries to clarify his location. “Hello? Sir? Sir, where are you at?” asks the operator.

Richardson told lead state prosecutor Linda Dunikoski that McMichael did not respond after that.

Dunikoski then played an earlier call, from July 13, 2019, in which McMichael identifies himself as a retired chief investigator for the district attorney’s office and asks to speak with a supervisor. He provides his contact number and home address, and tells the operator there have been several “break-ins” in the neighborhood.

“We got a lot of break-ins in this area, automobile break-ins. And my son and I just discovered a guy,” Gregory McMichael says. “We think he may be living under Bluff Creek bridge. We just made contact with him, a real shady looking fella and a possibility he may be the one that has been breaking into all of these automobiles around here.”

In a Jan. 1, 2020, call, Travis McMichael reports that a gun has been stolen from his truck. “I need a police officer, I need to report a stolen pistol,” he says.

On Feb. 11, just 12 days before Arbery’s killing, Travis McMichael tells a 911 operator that he has been sitting in his house watching a home construction site across the street when he spotted a man. There had been a “string of robberies” in the neighborhood, he says, and he describes the man as a “Black male in a red T-shirt and white shorts,” about “6 foot” tall.

“When I turned around, he took off running into the house,” Travis McMichael says in the call, adding that the man reached into his pocket, but he did not know if the man was armed. He advises emergency services to be “mindful” of that and leaves a contact number.

During the same call, Travis McMichael says he and several other neighbors were in the area and that the man tried to “sneak behind a bush.” He then notes that his gun had been stolen on Jan. 1 and that he had never seen the man in the neighborhood before.

Prosecutors brought forward other witnesses to the stand Wednesday.

Stephen Lowery, a former Glynn County police officer, provided details of his interview of Bryan that gave insight into the chase and what was going through Bryan’s mind when he encountered Arbery.

Prior to the incident, Lowery told prosecutors, he had not worked on any citizen arrest cases.

Larissa Ollivierre, a prosecutor, questioned Lowery as he read the transcripts from his interview of Bryan. Ollivierre displayed the transcripts on the screen as Lowery read.

Lowery said Bryan told him he angled his truck toward Arbery during the chase on the road and forced him to run into a ditch.

Bryan said Arbery’s handprints and fingerprints were on the outside of his truck. He told the officer he didn’t give Arbery “a chance” to get to his truck door before he angled him off the side of the road and drove past him.

Bryan then told Lowery he wished he had hit Arbery with his truck during the chase because it might have kept him from being shot.

“I didn’t hit him. I wish I would have. I might have took him out and not have got him shot,” he responded to Lowery.

Lowery also testified that Bryan never mentioned citizen arrest or an arrest for trespass during the interview.

Kellie Parr, who grew up in the Satilla Shores neighborhood, also took the stand and said there was no bullet hole in her parents’ window before the day Arbery was killed but there was after.

Parr told prosecutors she saw Arbery in the neighborhood in January in the house under construction. They looked at each other, and he did not run, she said. She said she thought to herself not to bother him or make any assumptions.

“I remember having a dialogue in my head,” Parr testified.

“I was driving by and I thought, ‘What is he doing in there?’ and then I thought, ‘No, Kellie, don’t be racist, he’s probably working on the house,’ and then I noticed he didn’t have a tool belt on. So I wondered what he was doing there,” she said.

But she kept driving she said, and did not make much of them making eye contact.

Arbery’s death sparked months of national outrage and protests throughout major cities in 2020. The trial, which began Friday, resumes Thursday, with the prosecution expected to continue to call witnesses.