It’s a club no one wants to join, and yet there is no shortage of members. In fact, there were almost too many to count prior to the advent of cell phones and hashtags. But for every Emmett Till or Rodney King, thousands are not as known. Definitely not as known as Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old Black teen, who, 10 years ago Saturday, was walking home from a convenience store when he was confronted and killed by George Zimmerman, a white Hispanic man who doubled as one part failed aspiring police officer and another part wannabe vigilante.

Trayvon joined a long list of Black women, men and children lost to senseless violence after being targeted for their race — but in 2012, America was a vastly different landscape from just a few years prior. The first Black president was fighting for his second term, the 24/7 media machine was becoming more polarized and politicized, and social media was so ubiquitous that the court of public opinion could gleefully weigh in on the worthiness of Black people in real time.

Trayvon was among the first Black deaths due to racialized violence to become a trending topic on Twitter. Since then, there have been so many men, women and children who have died and gone on to become hashtags that I can rattle off the list of names like a fourth-grader practicing for a state capitals test.

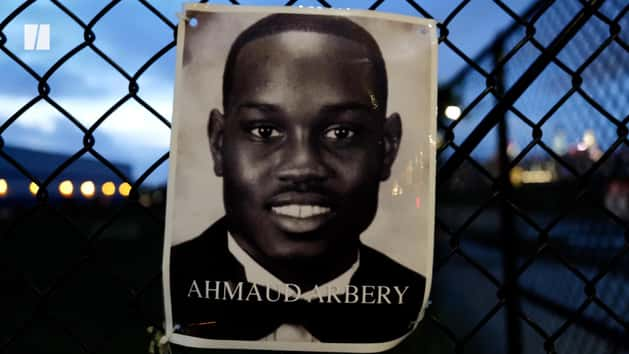

Michael Brown. Eric Garner. Sandra Bland. Philando Castile. Ahmaud Arbery.

When the crime is being Black in the wrong place, it becomes too easy to wonder who is next. Someone I know? Someone I love? Me?

White-on-Black violence wasn’t invented in the social media era, but one could argue it’s in the foundation of our nation. Four hundred years ago, white European settlers realized that after all but eradicating the Indigenous people of the so-called “New World,” they could ship in African peoples and have them do hard labor for free. It’s been a violent cycle since then.

And like all cycles, it’s taken a toll.

A 2018 study found that Black people reported poor mental health in the three months after a police shooting.

There’s the recriminations on cable news and on Twitter. There’s the fights over the Thanksgiving dinner table, the speculations, the memes and the trolling. (During the grand jury hearing for Darren Wilson, someone tweeted at me a photo that was allegedly of Michael Brown with a gun, as if that was supposed to prove something. I thought the Second Amendment was sacred?)

What does marinating in a never-ending cycle of violence against Black people do to the brain? What has a decade of this toxic soup of anti-Blackness done to us?

“The evidence is clear that discrimination matters for health,” David R. Williams, a public health professor at Harvard University and one of the 2018 study’s authors, said in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. “And it is not just what happens in the big things, like at discrimination at work or in interactions with the police. But there are day-to-day indignities that chip away at the well-being of populations of color.”

The idea that Black people have been experiencing collective trauma is not new, and wasn’t even brought on by the advent of the Internet. But in recent years, with the propensity for videos to go viral and the ability of everyone from your neighbor to the president of the United States to broadcast their opinion across the globe, the last 10 years have felt like a new phase of the problem.

“I am 18 now and I still hold the weight and trauma of what I witnessed a year ago. It’s a little easier now, but I’m not who I used to be,” Darnella Frazer, the teenager who filmed the murder of George Floyd, said on the first anniversary of the killing.

There’s a feeling that the violence against Black people and the subsequent barrage of media coverage is never-ending. While the nation and the people of Minneapolis waited for a verdict in the Derek Chauvin trial, Kim Potter, a white police officer, shot and killed 20-year-old Daunte Wright in the nearby suburb of Brooklyn Center. Even when people needed a break from police violence, the silence of the reprieve is interrupted with thoughts of the next one, as there’s always another one on the horizon.

If you’re not paying close attention, it’s easy to miss just how many trials and sentences have been handed down in the last few weeks. Kim Potter was sentenced to two years for the killing of Daunte Wright. The three other police officers involved in the death of George Floyd have been convicted of violating Floyd’s rights. The three white men who chased down and murdered Ahmaud Arbery have been found guilty of federal hate crimes. The trials pile up. The deaths pile up. The violence, it all weighs us down, sagging like the proverbial heavy load Langston Hughes once wrote about when asking what happens to a dream deferred.

In an NPR interview last year, psychotherapist April Preston described this type of trauma not as a simple, one-time thing, but as a complex trauma that encompasses multiple events often compounded by not being believed.

It doesn’t help that a wide swath of the country will justify any killing of a Black person. They shouldn’t have tried to fight back. Or maybe they should’ve just complied with the police. Never mind the fact that “do not comply” has become their rallying cry for opposing sensible public health measures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Not only is the threat of violence always lurking around the corner, the feeling that millions of people will say it’s your own damn fault looms large. It’s been 10 years since Trayvon was killed while walking home from a convenience store, launching the Black Lives Matter movement and ushering a new era of activism. Since then, countless more Black people have been lost to violence. And perhaps that’s the most traumatic part of all — the unshakeable feeling of dread knowing that it’ll happen again.

You just have to wait.